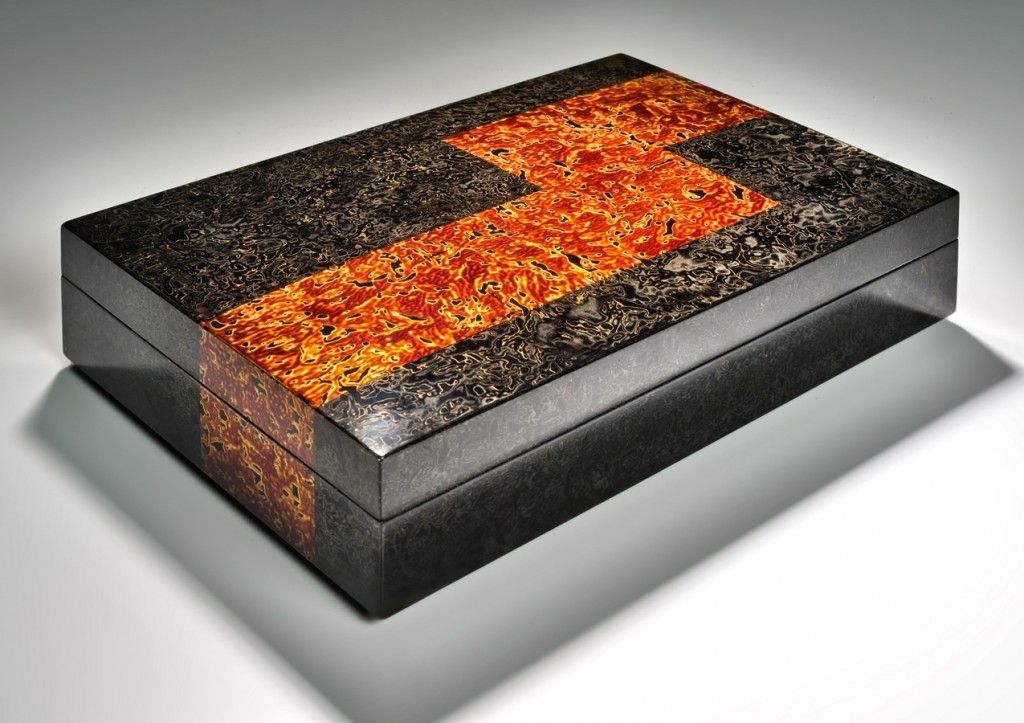

Work By Sergeij Kirilov

www.intarsio.nl

Learning by mistake

The solution might be staring you in the face but if you just can’t see it, what use is it? If the truth is too painful to listen to, you just can’t hear it. It is often claimed that you learn most from your own mistakes, but the paradox is that you have to admit to them. So do the quickest learners make the most mistakes? Are the slowest learners the people who make the fewest? Or do those who are most ready to admit their mistakes ascend vertically? What is best? Well, that all depends on what you are doing. If you are the catcher for a flying trapeze act or brain surgeon, may your mistakes be few and minor. Here it is better to learn from the mistakes of others. On the other hand, if you are an artist, you might depend on mistakes to make new discoveries. Selling slip-ups to the highest bidder. But intentionally making mistakes is trickier than it appears.

Not all laws are created equal

The applied arts exist in a stricter environment. If one table leg is too short, you are going to have to have a very convincing story to get away with it. It is easier to fix the leg than the mind of the buyer. The inevitable incessant wobbling will seldom be tolerated. Even if you, and your sense of humour, intended this to be the case. If every other detail is perfect, this single millimetre of discrepancy can bring the sum of your efforts crashing around your ears. This is obviously a mistake to learn from. So you do.

Tables start out with firm foundations but through years of use and mistreatment some develop a limp. Time and time again a piece of paper will be folded and slipped under the offending dangler. Without this rectification it is an unacceptable handicap. A table is too large to discard for such a small imperfection. Hard to ignore, it feels so wrong, it is so easy to fix. So you do.